Opinion analysis

on Jun 16, 2021 at 9:55 am

Sometimes, deep, conflicting social currents clash in titanic movements and romantic prose. Other times, they are submerged under rather drier land; underground rivers in a desert of language. On Monday, the Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, held that decades of roiling political turmoil surrounding the crack-cocaine epidemic could not compel a rereading of a single, highly consequential statutory clause, even if its primary authors pressed a different interpretation. Thus, in Terry v. United States, the Supreme Court held that low-level crack-cocaine dealers are not eligible for resentencing under the First Step Act, which in 2018 made higher-level offenders who received mandatory minimum sentences eligible for resentencing.

The opinion was written by Justice Clarence Thomas. One might speculate – and it is pure speculation on my part – that it was not coincidental that the court’s only Black justice was tasked with writing a case with deep racial implications. As recounted earlier, in 2008, Tarahrick Terry, then in his early 20s, was arrested in Florida for carrying just under 4 grams of crack cocaine. He was charged under 21 U.S.C. § 841(a)(1), which outlaws possession with intent to distribute crack cocaine, and sentenced under 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(C), a provision of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act that created a 100:1 disparity in the punishment of crack cocaine compared to powder cocaine. Section 841(b) sets forth three tiers of penalties, with Tier 3 offenses typically involving smaller amounts of drugs than Tiers 1 or 2. Terry was sentenced under Tier 3. Further, because he had two prior minor convictions as a teenager, he was punished as a “career criminal” and sentenced to just over 15 1/2 years imprisonment under the career-offender provisions of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines.

Even as Terry was being arrested, the political forces defining his punishment were being reexamined. The crack-cocaine disparity had largely come to symbolize an ineffective and counter-productive war on drugs and a racist criminal law system. After decades of political pressure, Congress finally reformed that sentencing regime in 2010 with the Fair Sentencing Act, which reduced the disparity to 18:1 and eliminated the mandatory five-year sentence for crack. In 2018, the First Step Act was passed, making sentencing reforms retroactive and past offenders eligible for resentencing.

The First Step Act applies retroactively to people sentenced for a “covered offense,” which is defined as any offense whose statutory penalties were “modified by section 2 or 3 of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010.” The explicit language of the Fair Sentencing Act increased the amount of crack punished as a Tier 1 offenses from 50 grams and above to 280 grams and above, and changed Tier 2 offenses from between 5 and 50 grams to between 28 and 280 grams. Though a natural reading would be that Tier 3 sentences, which punished “an unspecified amount of crack,” would now be those between 0 and 28 grams (rather than between 0 and 5 grams prior to the Fair Sentencing Act), the language of the Tier 3 provision was left unchanged. Leaving Tier 3 offenses unchanged results in the incongruity that offenders guilty of carrying large amounts of crack cocaine are eligible for resentencing, but low-level drug dealers, such as Terry, may languish in prison for decades. This reading, described as an oversight by the bill’s bipartisan principal drafters, resulted in a circuit split regarding whether an offender such as Terry had violated a “covered” offense that was “modified,” making him eligible for resentencing.

Ultimately, the court found he was not. Maintaining an arid reading of the statute, the court focused on two weighty, if technical-feeling facts, rather than a perhaps more unifying reading of the statute. First, the court held that the language under which Terry was sentenced was not modified by the sentencing-reform statutes. Although the change to levels above Tier 3 offenses would naturally invite one to think that the punishment of lower amounts of drugs should also be read differently, if the low-level provisions were not changed, they were not “modified.” And that is that!

Further, the court held that even though Terry was prosecuted for violating the federal law for intent to distribute crack cocaine, he was sentenced under the “career criminal” penalty regime in the Sentencing Guidelines, which remained untouched by the Fair Sentencing Act and the subsequent First Step Act.

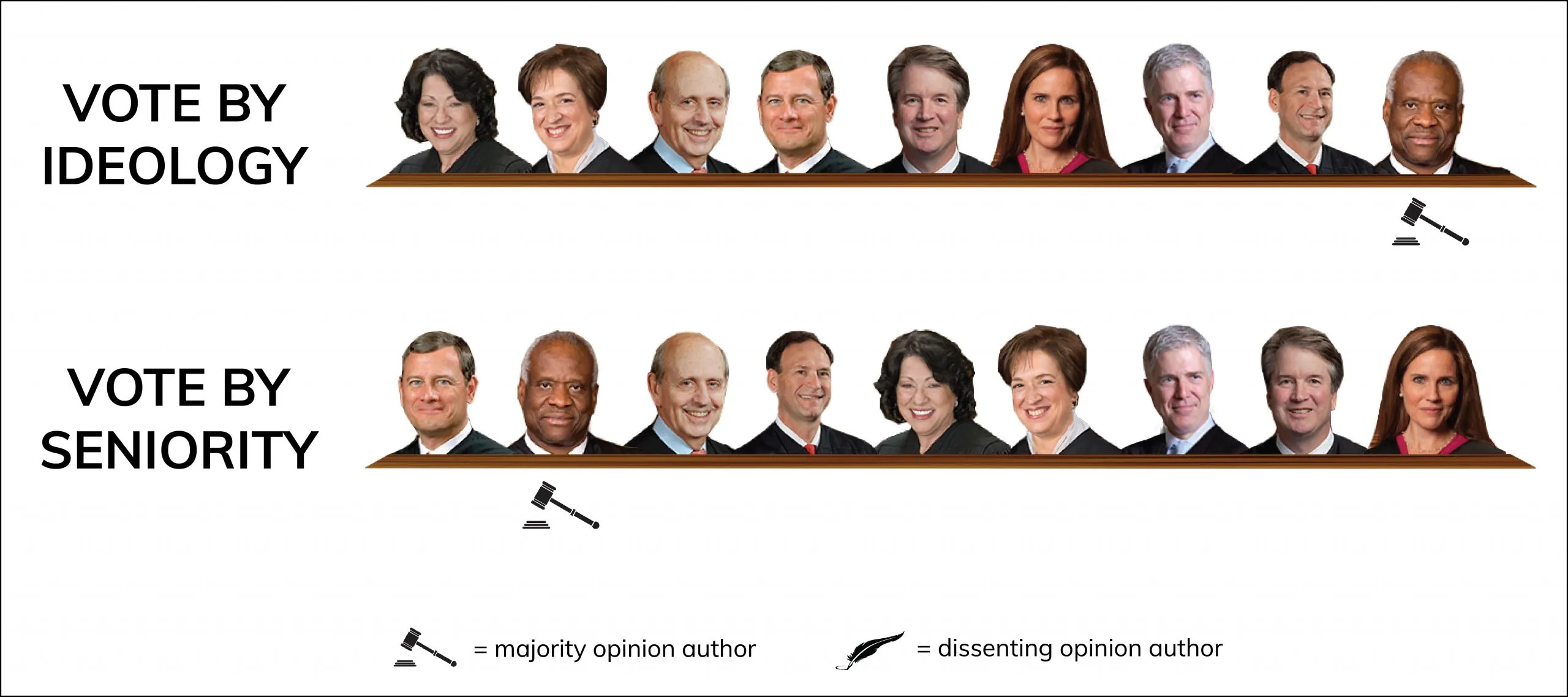

Reading the preceding sentences, it would seem hard to disagree that this was the only decision available to the court. And the decision’s unanimity may suggest, at first blush, that Terry represents neutral, nonpartisan judging rather than motivated interpretations. Yet closer inspection reveals the decision is not without evidence of the court’s ideological fault lines and does not satisfyingly resolve the basic incongruity with which the case started.

First, on the subtle signs of partisanship (or political valence or whatever term one prefers). The majority opinion begins by recounting the history that led to our current moment of sentencing reform. The history recounted is, as perhaps all histories are, a particularly shaped one, largely scrubbed of the contentiousness that marked America’s criminal-law response to the crack-cocaine epidemic. In the majority’s antique rendering, crack cocaine surged in America in the 1980s, bringing high-profile “cocaine-related” deaths and a wave of violent crime. The media, the public and Congress alike believed that crack was far more addictive and dangerous than powder cocaine and that America stood on the verge of a crack epidemic. Against this background, a nearly unanimous Congress, including large portions of the Congressional Black Caucus, quickly passed new tough drug laws, including the mandatory minimums and the massive 100:1 crack-cocaine/powder-cocaine disparity.

In this telling, it is only much later that Congress rethought the 100:1 punishment ratio, particularly in combination with the exorbitant sentencing guidelines. Further, the majority opinion confidently borrows an assertion in a Sentencing Commission report that racial animus had nothing to do with the sentencing regime; rather it was only the “perception of unfairness” to Black communities that caused congressional concern.

Absent in this telling is the realization that the apocalyptic media accounts of the crack epidemic might itself have been racialized, as thrown in stark relief by the vastly more sympathetic accounts of our current, much larger opioid crisis. Equally missing is the contentious support of Black elected officials, who, then as now, fought for tough-on-crime measures to be paired with social investment to address the root problems of addiction and crime, but instead were met with political investment overwhelmingly focused on policing. Absent also is the decade-long reversal of evidence purporting to show that crack is more addictive than powder cocaine. And most especially, the disproportionate impact of this sentencing regime on Black Americans and other people of color is barely mentioned.

It fell to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, in a bracing footnote in a solo concurrence, to correct the history, registering her objection so vividly as to note that she could not join that part of the unanimous decision.

What then of the fundamental incongruity at the heart of the case? Why would Congress provide a pathway for large players to seek resentencing while shutting out the lowest level street dealers?

The court ultimately held that the only question proposed by the First Step Act was whether Terry’s sentence was a covered offense, defined by violations modified by the Fair Sentencing Act. Since there was no penalty change for the minor offenders in Tier 3, they are simply not covered. Put (too) simply, 13 years ago, Terry was sentenced under Tier 3 of the statute – specifically, 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(C). Were he arrested and convicted today, he would still be sentenced under that precise provision. Congress’ peculiar treatment of these low-level offenses makes sense, the court offered, because those lowest level offenses (unlike the offenses in Tiers 1 and 2) never explicitly differentiated between crack and powder cocaine offenses and, thus, Congress did not need to correct any disparity. The natural implication that the congressional change to the punishments associated with the higher-level tiers shifted the punishment of the lowest-level crimes was dismissed as a “sleight of hand.”

In what read as a simple, almost dry, unanimous decision, it was left to Sotomayor to bring the human cost of the ruling to life. Rather than burying the legal contradiction, Sotomayor began her concurrence by pointing out the obvious: Had Terry been convicted of distributing a much larger amount of crack cocaine, he would currently be eligible for a sentence reduction. (In a vivid passage, she also illustrated the comparative weight behind the 100:1 disparity in punishment; for example, a half a stick of butter’s weight of crack cocaine was punished at the same level as a 1-gallon paint can’s worth of powder cocaine.)

Highlighting the long political battle to reform the crack/powder cocaine disparity, Sotomayor lamented that a congressional linguistic oversight has left some people accidentally behind. She made clear that the decades-long battle was due to more than a “perception of unfairness,” pointing out that between 80% and 90% of those imprisoned for crack offenses were Black, compared to about 30% of those imprisoned for powder-cocaine offenses. Her concurrence emphasized the scientific arbitrariness in treating these drugs differently and the decades-long urging of the Sentencing Commission to reform this disparity.

Sotomayor also dispatched the argument that Terry’s status as a career criminal placed him beyond a reformed sentence. Terry was sentenced as a career criminal because of two prior teenage drug offenses that netted him a total of four months in prison. It was these offenses that skyrocketed his next offense from what would have been 3 to 4 years in prison to between 15 and 20 years in prison, throwing away the life of another young, Black man. The interaction between the baseline disparities for crack-cocaine offenders and the career-criminal guidelines provide policy reasons to apply the reforms broadly – not to render ineligible those who have been so harshly sentenced. As Sotomayor noted, over half of those who received sentencing reductions in the first year of The First Step program were sentenced under the career-criminal statutes.

Sotomayor’s concurrence makes clear that dismissing Terry as one of a few who ought to be eligible for sentencing reform but slipped through the cracks does an injustice to the hundreds of other similarly situated people who will collectively spend uncountable years in prison serving disproportionately large sentences. Yet ultimately she joined the court in ruling that the current language of the First Step Act, peculiar as it may be, would not “bear [a] reading” that allows for the lowest-level drug dealers to have their sentences reformed. The hope, Sotomayor concludes, is that Congress now takes up its pen to complete its work.

"heavy" - Google News

June 16, 2021 at 08:55PM

https://ift.tt/3cIkyZV

Unanimous ruling on crack-cocaine disparity is heavy on text, light on history - SCOTUSblog

"heavy" - Google News

https://ift.tt/35FbxvS

https://ift.tt/3c3RoCk

heavy

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Unanimous ruling on crack-cocaine disparity is heavy on text, light on history - SCOTUSblog"

Post a Comment