In the summer, coronavirus cases were surging across the Bay Area. Now, they’re surging again. But will this round prove worse than before?

While the Bay Area overall has tended to do an effective job of controlling the virus throughout the pandemic, experts are deeply concerned about the trajectory of this latest surge.

“Given that we’re almost at the (summer) peak, even if we were to start aggressive intervention now, it’s very likely the total number of cases will exceed the worst numbers the Bay Area has ever seen so far,” said Robert Siegel, an infectious disease expert at Stanford University. “As these rates go still higher, it looks like we’ll join the rest of the country in the worst rates we’ve ever had in the pandemic.”

The worst rates for the Bay Area may not approach the devastation that unfolded in New York City early in the pandemic, or what’s happening now elsewhere in the country. Still, hospitalizations due to COVID-19 across the Bay Area have increased 38% since the beginning of November, with more than 400 patients for the first time since Sept. 23.

And, as many experts have said throughout this pandemic, the virus knows no boundaries.

“The whole state is experiencing this crush of cases, indeed the entire country is experiencing this crush of cases,” Santa Clara County health officer Sara Cody said in a news conference Monday. “In the past, we knew that we could rely on asking for help from other jurisdictions if we needed it. That’s not the case now because everyone is quite busy attending to their own residents and their own communities.”

Shannon Bennett, chief of science at the California Academy of Sciences, said rapid spread in rural parts of states that didn’t see big summer surges could have an exponential impact on California, as residents are widening their pods and moving around more.

“As the whole nation heats up, we’re going to be more at risk for bringing the virus into the state,” she said.

She said Californians may feel that they have been good throughout the pandemic, and decide to travel to a place where there is a “huge disparity in public messaging and government leadership.” That, she said, could in turn worsen the surge in the Bay Area.

Here are the main factors that make today’s situation different from the summer surge, and potentially more dangerous.

What’s different about this surge

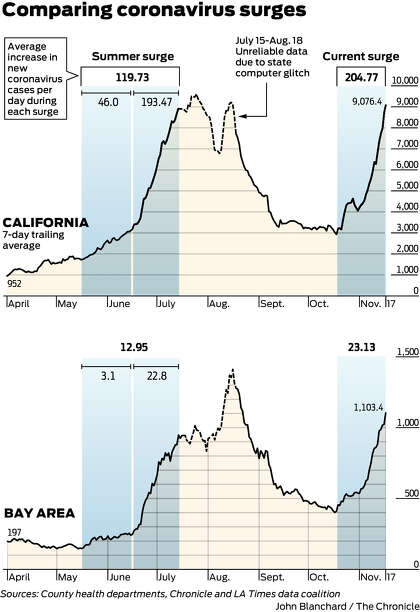

To analyze how the current increase in cases compares to the summer surge, we looked at the average increase in new cases per day, which shows not just the mounting cases but the pace at which they are increasing.

From mid-May to mid-June, the period when cases first started to climb in California, the average increase in daily new cases was 46 stateside. From mid-June to mid-July it shot up to 193.5. In the Bay Area, the curve stayed flat longer and the number of new cases went from 3.1 early in the surge to 22.8 over the second half. (On July 15, a computer glitch in the state reporting office occurred, making data for the following few weeks unreliable with unreported cases followed by the clearing of large backlogs.)

Compare those numbers to the data from mid-October, when the latest surge in California began, to now, covering a span of 30 days: The average increase of new cases per day was 204.8 statewide, and 23.13 in the Bay Area. Both of those numbers are higher than during the final 30 days of the previous surge.

According to health officers, the primary factor driving this current surge appears to be social gatherings, with more people heading indoors as the weather cools. Many counties also point to pandemic fatigue in communities as people tire of sheltering in place and abiding by restrictions.

Unlike previous surges, the current one appears to be impacting a broader swath of people across the Bay Area.

In the summer, the spread was concentrated among groups including agricultural and factory workers, nursing homes and other congregate living facilities, Siegel said. Cases have disproportionately affected essential workers and communities of color, particularly the Latino populations in many counties.

Now, the spread is occurring everywhere.

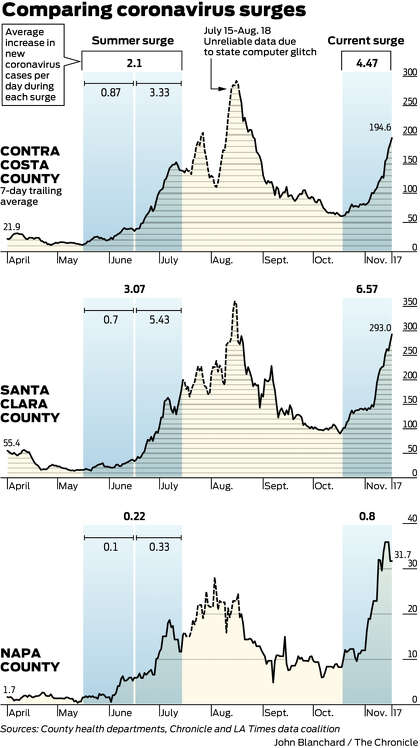

In Contra Costa, for example, the summer surge was concentrated in communities of color and among essential workers.

“The surge we are seeing now is still hitting those communities hardest, but we are seeing increases in every community, so it is more widespread this time,” said Karl Fischer, spokesperson for Contra Costa Health Services.

The average increase in new cases per day was 2.1 in the summer surge, spiking to 3.3 during its height. Now, it is 4.5.

Fischer said this current surge shows a “rapid increase.” He said the county’s positive test rate and hospitalizations have also increased significantly in the past month.

In Napa, the peak case rate over the summer was 20.7 per 100,000 people. In the last week, the rate has gone as high as 26.3, the highest rate the county has seen so far, according to health officer Karen Relucio. (These rates are not the figures the state uses for reopening tier assignments, which are adjusted based on the number of tests performed in a county.)

In a presentation to the Napa County Board of Supervisors on Nov. 10, Relucio said a lack of cooperation with contact tracing has resulted in 35% of cases that are of unknown origin, which stunts the county’s ability to control the spread if they don’t know where the virus is coming from. Other drivers include household transmission, gatherings and travel outside of state.

The public messaging is empathetic, but also more direct now as the situation becomes more dire, Relucio said.

“Wishful thinking and complacency will not make the pandemic go away,” she said. “It’s past time for people to take personal responsibility, redouble their efforts and realize their actions affect others.”

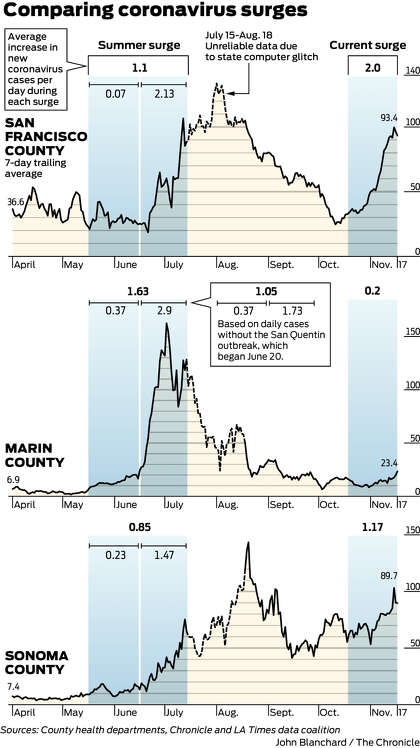

In Marin County, health officer Matt Willis said the summer surge was concentrated in the essential worker population, primarily the Latino community, where many individuals were exposed at work and then brought the virus home. But recently, case rates in the essential worker and Latino communities appear to be steady.

“What seems to be driving cases now over the last three weeks is more cases among our white residents,” he said. Cases are more geographically spread across the county now, and they are being increasingly driven by social gatherings.

“The weather has just started to turn cold, we haven’t seen any influenza yet, the real holidays haven’t even begun, we’re still bringing children back in the classrooms and facing a lot more travel,” Willis said. “What’s particularly concerning is that this very rapid acceleration has preceded those things that we were most concerned about.”

Marin County, which dealt with the San Quentin outbreak in the summer, only recently started to see a rise in cases during this latest surge.

Why this surge may be more dangerous

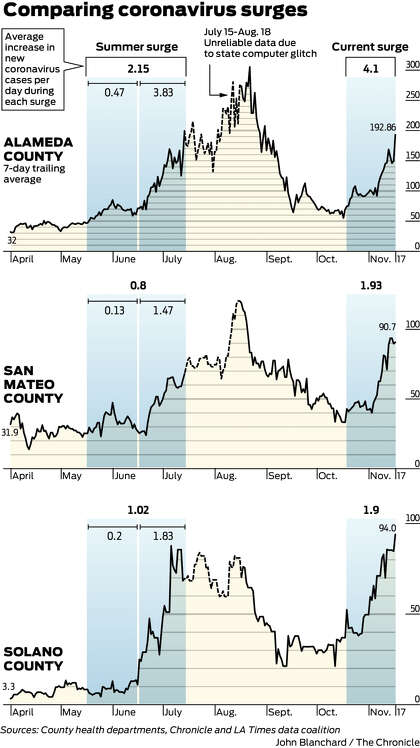

Another worrisome factor in the Bay Area’s current spike is that it started with higher numbers compared to the period before the summer surge. A steep curve starting from a small number of cases is less dangerous compared to a steep curve starting from a lot more cases, Siegel said.

“That is manifest in the fact that many populations are being infected that were uninfected before,” he said.

During the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors meeting Tuesday, health officer Dr. Sara Cody noted several differences in the current surge versus the summer surge, including that the county never got back to the low baseline reached in May.

“The rate of rise has been both steeper and faster than any of the previous increases that we have been experiencing here or elsewhere in the state,” she said.

In San Mateo County, congregate care facilities accounted for the bulk of coronavirus cases early on. The county sent support teams to assist with staffing and establishing isolation and quarantine protocols, which greatly helped reduce the numbers. Now, cases are rising among younger people, said Louise Rogers, chief of San Mateo County Health.

“Now we’re focused on really driving the message home to residents,” she said. “It’s our behaviors that are really key to beating back the virus right now, which includes wearing face coverings and avoiding gathering over holidays to protect the safety of our loved ones.”

Rogers said the county is in better shape now to address the surge than before, with supports in place including PPE, testing, hotel rooms and other infrastructure.

Willis said Marin County plans to triple staffing for contact investigation, mobile testing and testing results teams.

San Francisco officials have been preparing since the start of the pandemic for the possibility of more hospitalizations, and ensured hospitals have discussed and reviewed surge plans, said health department deputy director Naveena Bobba.

“The most recent surge demonstrates that this is bigger than any one county or any one region,” Rogers said. “I don’t have a crystal ball, but I’d really like to see the Bay Area set the course and demonstrate how to flatten this curve again.”

Kellie Hwang and Mike Massa are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: kellie.hwang@sfchronicle.com, mmassa@sfchronicle.com

"current" - Google News

November 19, 2020 at 07:00PM

https://ift.tt/3pJmcja

Charts show how Bay Area’s current coronavirus surge is already worse than the last one - San Francisco Chronicle

"current" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3b2HZto

https://ift.tt/3c3RoCk

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Charts show how Bay Area’s current coronavirus surge is already worse than the last one - San Francisco Chronicle"

Post a Comment